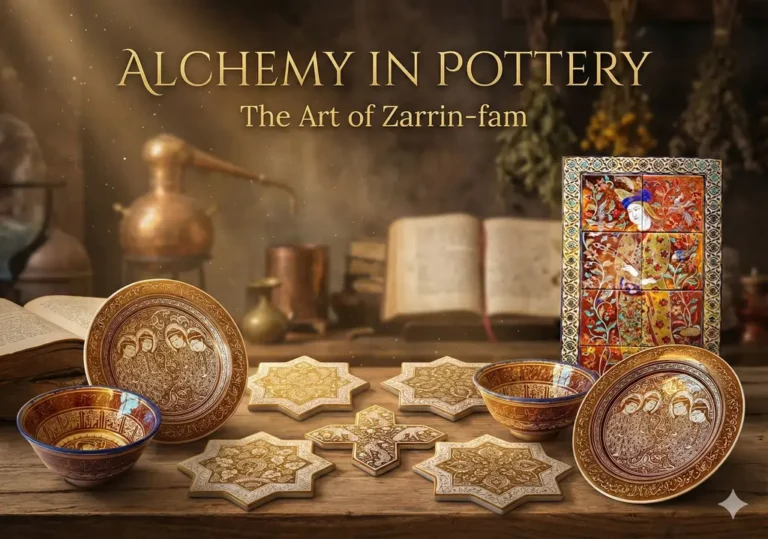

Introduction When we look at a piece of Lusterware (Zarrin-fam), we are often blinded by its golden shine. But if we look past the reflection, we discover something even more valuable: a story. Unlike ordinary kitchenware, Lusterware ceramics produced in the Golden Age of Iran (and revived today by masters in Natanz) were never just about function. They were “talking objects.”

The intricate designs, the circle of calligraphy around the rim, and the strange figures in the center are not random decorations. They are a visual language. They speak of love, mysticism, ancient myths, and the fleeting nature of life. In this article, we will act as archaeologists of art, decoding the symbols and poems that have been baked into these golden vessels for centuries.

1. The “Moon-Faced” Beauties: The Human Figure

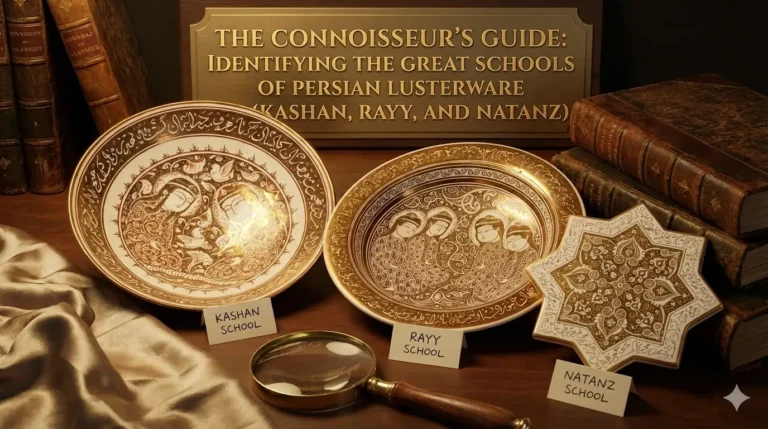

One of the most striking features of Iranian Lusterware (especially from the Seljuk and Ilkhanid periods, 12th–14th century) is the depiction of people. You will often see seated figures with round faces, small mouths, and almond-shaped eyes.

The Turkic Ideal: This specific facial type is known as the “Moon Face” (Mah-ru). It reflected the standard of beauty at the time, influenced by the ruling Turkic dynasties.

The Courtly Life: These figures are rarely working. They are shown sitting, drinking wine, playing instruments (like the oud or harp), or listening to poetry.

Symbolism: These scenes represent the “Garden of Pleasure”. In Sufi interpretation, this earthly joy is a metaphor for the spiritual ecstasy of being close to the Divine. The wine cup is often a symbol of the “Wine of Love” (spiritual intoxication).

2. The Talking Pottery: Calligraphy and Poetry

Lusterware is famous for being “literary ceramics.” Almost every fine bowl or tile features a band of writing, usually around the rim or on the border.

Unlike mosque tiles which feature Quranic verses, Lusterware vessels usually feature Persian Poetry.

Rubaiyat (Quatrains): Short, four-line poems are very common. They are often by poets like Baba Tahir or anonymous romantic poets.

The Message: The poems often talk about the transience of life. For example: “Drink from this bowl today, for tomorrow we may be clay.” This creates a profound irony: the user is drinking from a clay bowl, reading a poem about turning into clay!

Social Function: These bowls were used in gatherings (Majlis). As the bowl was passed around and the food was eaten, the writing would be revealed, sparking conversation or recitation among the guests.

3. The Simurgh and the Animals

Animals in Zarrin-fam are never just decoration; they are mythical symbols rooted in ancient Persian culture.

The Simurgh: A mythical winged creature (similar to the Phoenix). It represents divine protection and the union of all souls. In the famous poem The Conference of the Birds, the Simurgh is God. Finding a Simurgh on a Luster tile implies a spiritual journey.

The Gazelle: Often shown running or trapped in foliage. It symbolizes the human soul, beautiful but fleeing, trapped in the tangled “thorns” of the material world.

Fish and Water: In the center of many bowls, you might see fish swimming. This represents the “Water of Life.” Since the bowl held liquid, the design playfully interacted with the contents.

4. The Infinite Garden: Arabesques and The Tree of Life

When there are no figures, Lusterware is covered in complex, intertwining vines known as Arabesques (Eslimi).

The Geometry of God: These patterns have no beginning and no end. They repeat infinitely. This is a visual representation of Tawhid (the Oneness of God) and the concept of infinity.

The Cypress Tree (Sarv): A very common motif in Natanz and Kashan pottery. The Cypress tree bends but never breaks. It is evergreen. It symbolizes freedom, eternity, and truthfulness. In the Tavallian workshop’s modern adaptations, you will often see the Cypress as a nod to this ancient identity.

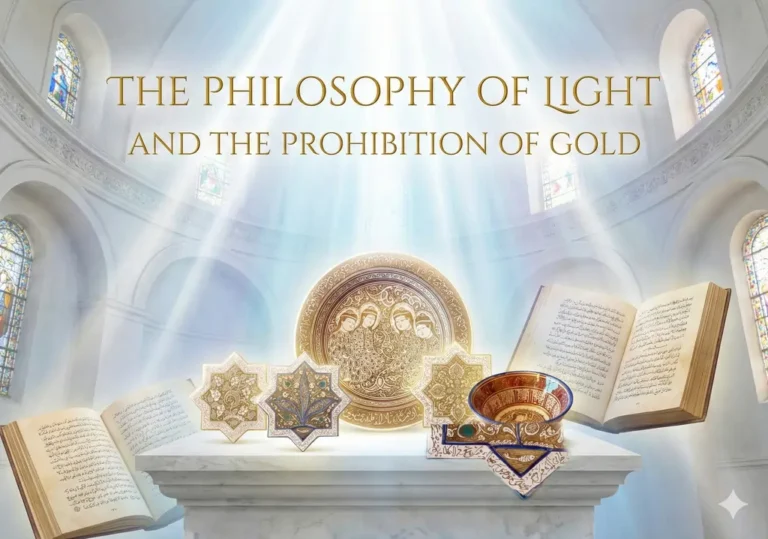

5. The “Sunburst” Design: Light upon Light

Some Lusterware plates feature a central sun-like design with radiating rays. Given that the technique itself is about reflecting light, this design amplifies the effect. It turns the plate into a miniature sun. This connects back to the philosophy of Illuminationism (Hikmat al-Ishraq) popular in 12th-century Iran, where Light is the essence of all creation.

Conclusion: Reading the Clay

When you hold a piece of Lusterware—whether an antique from a museum or a contemporary masterpiece from a traditional workshop—you are holding a book. The “Golden Ink” tells us what the people of the past loved, what they feared, and what they believed in.

These designs remind us that art is not just about making things look pretty; it’s about making matter speak. The potters of Natanz and Kashan didn’t just shape clay; they wrote poetry with fire.