Lusterware (Kashan, Rayy, and Natanz)

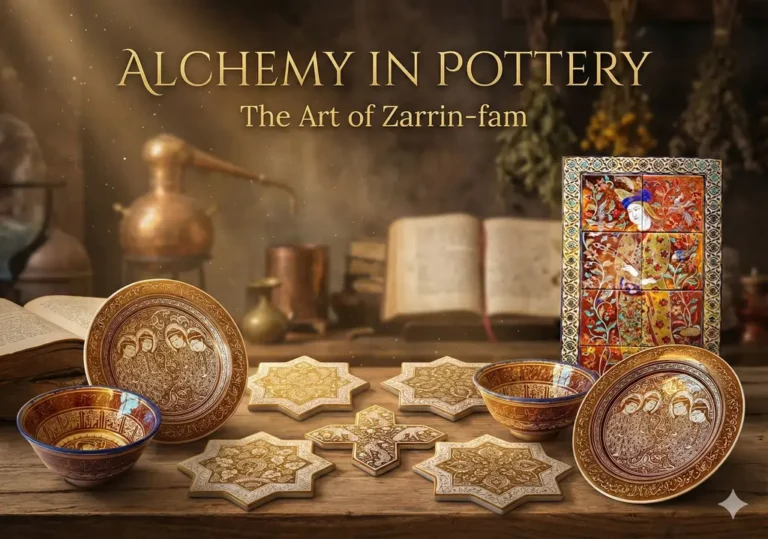

To the untrained eye, all lusterware might look the same: beautiful, golden, and antique. But to the expert collector or art historian, a bowl from Rayy speaks a completely different language than a tile from Kashan. Just as European painting has distinct schools, such as the Venetian and Florentine styles, Persian lusterware (zarrin-fam) also developed unique regional fingerprints. During the Golden Age of Iranian ceramics between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, different cities created their own chemical formulas, painting methods, and aesthetic philosophies. In this final article of the series, we explore how to distinguish the monumental style of Rayy from the intricate style of Kashan and examine the enduring legacy of Natanz.

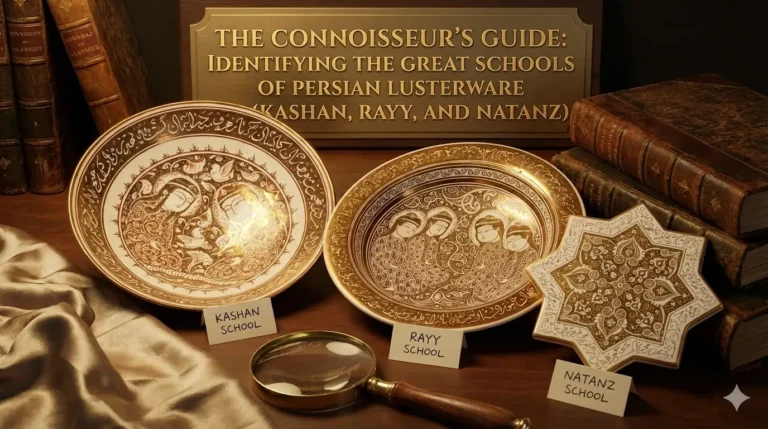

Rayy, located near modern-day Tehran, was once a major royal capital before its destruction by the Mongols. The lusterware produced in this city is often considered the boldest and most visually powerful. Rayy artists frequently used the reserve technique, painting the background in solid luster while leaving the main figure in the white of the base glaze, which resulted in a dramatic, silhouette-like contrast. The human figures are large and monumental, usually occupying the entire center of the vessel and appearing uncrowded. The drawing style is fluid and sketch-like, revealing the speed and motion of the artist’s hand and emphasizing energy over fine detail. The luster palette of Rayy tends toward reddish-brown or deep copper tones, reflecting a bold and imposing aesthetic closely associated with the grandeur of the Seljuk court.

Kashan, by contrast, represents the most refined and technically perfected center of lusterware production. The very Persian word for tile, kashi, is derived from its name, and the city was home to renowned potters such as the Abu Tahir family. Kashan wares are immediately recognizable by their horror vacui, or fear of empty space, in which every surface is densely filled with minute spirals, dots, scrolling vegetation, and birds. Human figures are usually small and often grouped together, set against extremely busy backgrounds. A distinctive feature known as the “Kashan halo” appears as a solid white area behind the heads of figures, allowing them to stand out from the surrounding ornamentation. Clothing is richly patterned with textile-like designs rather than left plain, and the chemistry of the luster was highly standardized, producing consistent golden-yellow or olive-gold tones. Artistically, Kashan pottery parallels the tradition of manuscript illumination, inviting slow and meditative visual engagement.

For many years, archaeologists uncovered remarkably well-preserved lusterware in the city of Jorjan, near the Caspian Sea, often stored inside large clay jars buried underground. This led to debate over whether Jorjan had its own kilns or whether Kashan merchants transported their finest wares there for safekeeping in anticipation of the Mongol invasions. The prevailing scholarly view today is that these objects are Kashan products rather than a separate local school. Their exceptional condition is attributed to centuries of protection inside sealed jars, and the term “Jorjan style” generally refers to high-quality Kashan lusterware with unusually pristine preservation.

Unlike Rayy, which was destroyed, and Kashan, whose production gradually declined, Natanz emerged as a resilient center that continued the tradition of lusterware into the Ilkhanid and Timurid periods and, remarkably, into the modern era. Natanz ceramics often synthesize elements of Kashan’s dense decoration with more geometric and architectural compositions. The city is particularly famous for its architectural tiles, exemplified by the complex luster tiles in the tomb of Sheikh Abd al-Samad, which demonstrate advanced techniques in molding, relief work, and three-dimensional tile production combined with luster painting. In later Natanz wares, cobalt blue and turquoise glazes appear more frequently alongside golden luster, adding chromatic richness. Unlike the extinct historical schools, the Natanz tradition survives through families such as the Tavallians, who preserve localized knowledge of clay sources and glaze recipes passed down through generations.

Understanding these regional styles transforms lusterware from mere “shiny pottery” into a profound historical document. A bowl from Rayy embodies the bold confidence of the early Seljuks, a tile from Kashan reflects the height of scientific and artistic precision, and a piece from Natanz represents endurance and continuity in the face of political and cultural upheaval. Whether for collectors or students of history, recognizing these distinctions honors the individual artists who, centuries ago, turned the soil of their own cities into lasting gold.