The Great Migration of Gold: The Historical Journey of Lusterware from East to West

- Alireza

- No Comments

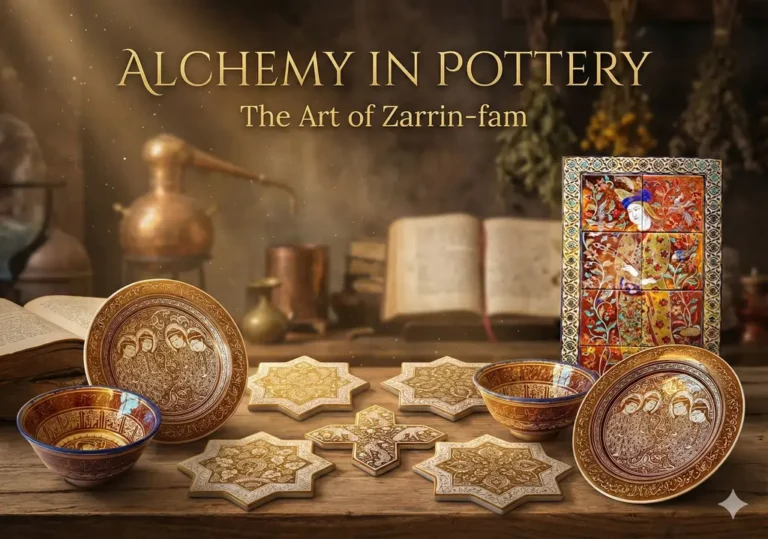

Introduction Art is rarely static; it moves, migrates, and evolves along with the people who create it. In the history of ceramics, no technique has traveled a more fascinating path than Lusterware (Zarrin-fam). This complex technology—the art of painting with metallic smoke—did not just appear everywhere at once. It was a closely guarded secret that traveled along the Silk Road and the Mediterranean trade routes, sparking artistic revolutions wherever it landed.

From the banks of the Tigris River to the palaces of Granada in Spain, and finally to the workshops of the Italian Renaissance, Lusterware connects the East to the West. In this article, we trace the 1,000-year journey of this “ceramic gold” and discover how Iranian masters influenced the art of Europe.

1. The Birthplace: Abbasid Iraq (9th Century)

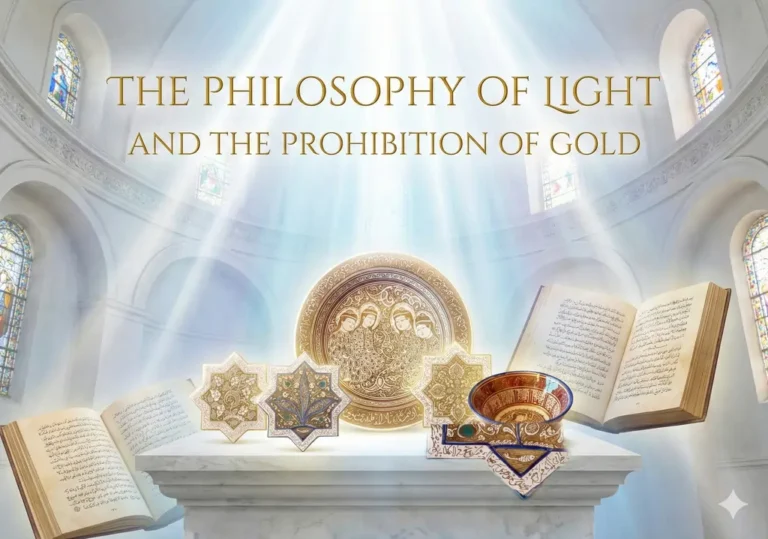

The story begins in the 9th century in Basra and Baghdad (modern-day Iraq), under the Abbasid Caliphate. While the exact origins are debated, most scholars agree that this is where the technique was first applied to pottery. Before this, luster was only used on glass in Egypt.

The Iraqi potters were the pioneers. They produced “Polychrome Luster” (multi-colored), using ruby reds, greens, and golds on a single vessel. It was here that the initial chemistry of silver and copper reduction was perfected to satisfy the court’s demand for luxury without violating the prohibition on real gold.

2. The Egyptian Chapter: Fatimid Splendor (10th–12th Century)

With the decline of the Abbasids, the master potters—who were likely a small guild of families guarding their secrets—migrated to Cairo (Fustat), the capital of the Fatimid dynasty.

Here, the style changed dramatically. The Fatimid era is known for:

Figurative Art: Unlike the abstract designs of Iraq, Egyptian lusterware featured lively scenes of dancers, musicians, animals, and hunting.

Monochrome Style: The multi-colored palette was largely replaced by a rich, consistent golden-olive tone.

However, the burning of Fustat in 1168 AD forced the potters to flee once again. This tragedy led to the greatest era of Lusterware history.

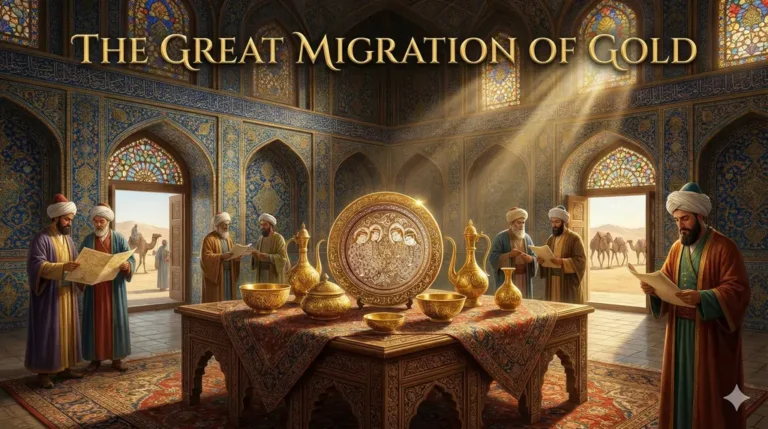

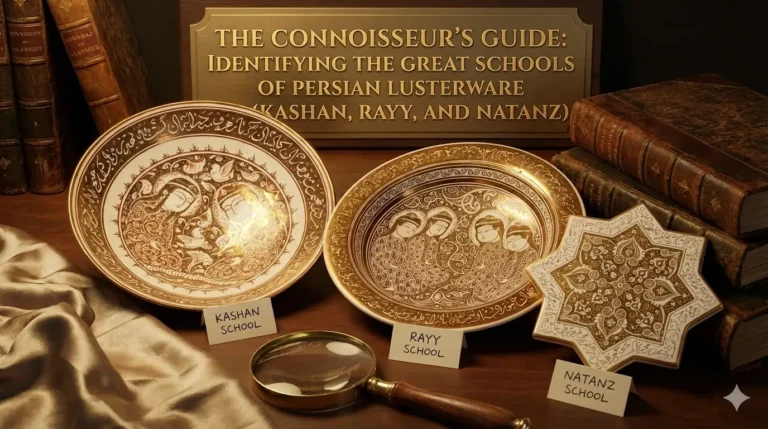

3. The Iranian Zenith: Kashan, Rey, and Natanz (12th–14th Century)

The potters migrated east to Iran, settling in cities like Rayy, Kashan, and Natanz. This period (Seljuk and Ilkhanid eras) is considered the “Golden Age” of Lusterware.

Iranian masters took the technique to unmatched heights:

Monumental Art: They moved beyond bowls and plates to create massive Mihrabs (prayer niches) and wall tiles for shrines.

Literary Integration: Persian poetry was inscribed onto the borders of tiles.

The Kashan Families: Famous families, such as the Abu Tahir family, signed their works. This tradition of family lineage continues today in places like Natanz (with families like Tavallian).

It was in Iran that the chemistry became standardized, and the famous treatises (like that of Abul-Qasim Kashani) were written, preserving the formulas we know today.

4. Crossing the Mediterranean: Andalusia and the “Hispano-Moresque”

While one branch of the art flourished in Iran, another branch moved West across North Africa into Muslim Spain (Al-Andalus).

By the 13th and 14th centuries, the cities of Malaga and Manises became production hubs. The famous “Alhambra Vases”—giant, wing-handled vases covered in golden luster—were created here. This style, known as Hispano-Moresque, combined Islamic geometric patterns with European heraldry (coats of arms).

This was the bridge to Europe. Christian kings and queens, including the Popes, began commissioning these “golden pots” from the Moorish potters of Spain.

5. The Italian Renaissance: The Birth of “Maiolica”

The Italians were obsessed with the golden pottery coming from Spain. Since the ships carrying these goods often stopped at the island of Majorca, the Italians called the pottery “Maiolica.”

Driven by jealousy and admiration, Italian potters in cities like Gubbio and Deruta spent years trying to reverse-engineer the Islamic technique. In the 16th century, they finally succeeded. The famous Italian Renaissance lusterware is a direct descendant of the techniques invented in Iraq and perfected in Iran.

Conclusion: A Universal Language

The journey of Lusterware is a story of Technology Transfer. It proves that science and art have no borders. A formula for copper reduction written in Arabic in Kashan eventually found its way to a workshop in Italy, changing the face of European art.

Today, when you hold a piece of Lusterware from a traditional workshop in Natanz, you are holding the survivor of this incredible journey. While the fires have gone out in Fustat and Malaga, the kilns in Iran are still burning, keeping this 1,000-year-old global heritage alive.